Milestones in Music History #1: Zang Tump Tump! The Birth of Noise

Noise Music; Barret; Suicide; Velvet Underground; Desert Rock; the history of music is a perilous and yet appeasing path to walk. It has been, since the dawn of time, this powerful gift—and music is possibly the most evolving and sophisticated form of art, which affected culture, lifestyle, society, the history itself. The purpose of this new series Milestones in Music History is to delight you with some of the pivotal moments in music, some acts, facts, and records which delineated and shaped the music for the years to come (actually as far as this series could go on). I have selected a few, based on my personal path through music culture, and because I firmly believe these moments radically changed... everything. In today's episode, I would like to lead you to the very origins of electronic music: noise.

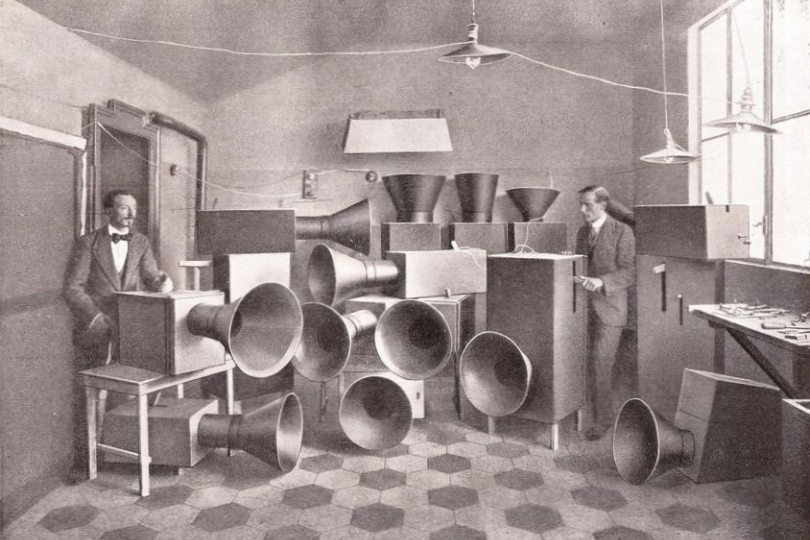

Futurist noise machines

Italy, 1913: the Futurist manifesto L’arte dei Rumori ("The Art of Noises") appears, drawn up by Luigi Russolo. In the same year, Russolo performs in Villa Rosa, which is owned by Filippo Tommaso Marinetti—another prominent exponent of the Italian Futurist movement—with his Intonarumoris noise machine. The year after, the noisy experiment is followed by Giacomo Balla’s "Typewriter."

These two experiments act as a detonator in the history of music. Futurism is important for the development of the noise aesthetic, as is the Dada art movement. On April 30, 1919, the Antisymphony concert—a celebration of Dada spirit—takes place in Berlin.

In my opinion, this is where we can start talking about electronic music (and also about noise music, or, as the French define it, bruit). In Italy the futurists praise noise, understood as the sound of everyday life that smashes the graceful (and perhaps even repetitive and, in some ways, banal) succession of seven musical notes.

Musique concrète

In the meantime, in 1932, some exponents of the Bauhaus movement experiment with modifying record grooves through the modification of their physical content. In 1940, Pierre Schaeffer coins the expression musique concrète to identify all modifications and interpolations made on original tapes and recordings through the use of noise and manipulation techniques. He also composes his "Five Noise Etudes," which consists of modified locomotive sounds.

The search for sound—or rather, noise—is not only carried out through the search for disparate sounds with classical instrumentation, but also through the manipulation of objects of common use and with junk.

The work of Henry Cowell, Lou Harrison, and John Cage in US in this field is remarkable. In 1939 John Cage starts his own series of Imaginary Landscapes, in which he combines recorded sounds, several percussions and, as in the case of Imaginary Landscape No. 4 (March No. 2), a work that premiered in New York in 1951, he creates a performance for twelve radio receivers.

His most famous work 4’33’’ is a provocative silent composition, where the absence of music is what actually generates the sound itself—real or imagined.

In Cage's 1960 composition Cartridge Music, the performer is instructed to insert all kinds of small objects into the cartridge of a phonographic pick-ups fitted with a needle.

"The music of noises" and its relevance today

These early experimental and, in some ways, extreme works mark a turning point in the artistic process and in the conception of music itself and of the artist. The world of everyday life and reality, of small objects, instinct and unconscious impulsiveness; all these themes are the object and point of interest of the music of noises. The artist disappears in the din of the city and in the confusion of the modern frenzy, but he does not dissolve completely. He becomes the expression of his art and the sound becomes an expression of his life. Since the sound of everyday life is not melodic but pungent, annoying, sometimes unbearable, but familiar—then the final musical product will be exactly like that.

The noises of everyday life are unnerving but well-known, they haunt us, but at the same time confer a space-time identity and a representation of the man who lives in the world, projected into technology.

The development of musical instrumentation and the digitization of sound causes a thunderous diffusion of noise in contemporary music.

In more recent times, genres as noise rock, no wave, industrial, Japanoise, and postdigital music (glitch, among all) exalt the noise component in music, giving space to distorted and dissonant compositions.

The invention of noise, which obviously has always existed but never elevated to art, generates a new musical poetics, and overturns the ordinary mechanism of composition.

The succession of sounds—sometimes unrepeatable, because they are unreproducible, or because they simply cannot be planned—leaves room for the logic of chance.

Furthermore, the music of noises, precisely due to its inability to be reproduced and performed, acquires the highest level of art, precisely due to the impossibility of reproducing the compositions, of making "covers."

Today, experimental and noisy music knows many contaminations. One of the most interesting bands to perform through the utilization of industry machines and improvised noised is Einstürzende Neubauten. Among the most sublime artists in this field, I certainly would like to mention at least Alva Noto and Ryuichi Sakamoto, but also projects that are a little more techno and extreme, such as Amnesia Scanner.

The noise universe is so vast and fascinating that one whole series would not cover all of it. But the evolution of those first futurist and dadaist music experiments leads inevitably to the experimental music of the '60s, in particular the work of a pioneer of experimentation (as well as noise), who definitely took the wheel in the craze maze of the psychedelia: Syd Barrett. So stay tuned for part #2 in the series Milestones in Music History!

What do you think of "the music of noises?" Are you familiar with such projects? How do you think that noise music can coexist with what we commonly call "Music?" Leave us your opinion below in the comments!

If you have found an error or typo in the article, please let us know by e-mail info@insounder.org.