(Un)usual Guitar Techniques #9: String Harmonics

After two episodes dedicated to very fast playing, we can take a breather and look at a technique that shapes the fundamental character of tone. And although these wailing sounds appear mainly in the harder genres, lovers of quiet, strong melodies or bluesy licks might also appreciate them. We'll talk about the string harmonics or flageolets, which may be a bit of a pain at first, but once you learn to use them, you'll awaken an untamed creature bursting with energy in your guitar.

Most of us associate string harmonics or flageolets with acoustic or even classical guitars, or with their tuning. However, they also appear in electric guitar playing. First, let's clarify the terminology that describes many of the sounds solo guitarists make.

Natural and artificial harmonics

On a stringed instrument, natural harmonics occur when the string is not pressed down at the corresponding point on the fingerboard but only touched lightly. This divides the vibrating string into regular (half, third, quarter, etc.) parts and produces a series of aliquot notes, i.e. higher harmonic tones which resonate with the fundamental tone, determine the characteristic timbre of the instrument's sound, and occur naturally in almost every note. In tablature, natural harmonics are abbreviated NH.

The lowest aliquot tone, sounding above the fundamental tone, is the octave, which resonates when the guitar's empty string is muted at the 12th fret. Other distinctive NH can be found at the 5th and 7th frets of the guitar. A well-known use of natural harmonics is during guitar tuning: the NH above the 5th fret of the lower string of a tuned guitar sounds the same as the NH above the 7th fret of the higher string, and vice versa (this doesn't apply to the G and B strings).

The artificial harmonics or AH is created similarly, but instead of the zero fret, we use a pressed tone on the fingerboard. This requires more practice, because to get the best sound, you have to press the string again in the middle, quarter and so on. Of course, this position changes depending on which fret you press the string on. You'll always find it an octave higher than the note you played. With the index finger of your right hand, you mute the string in the corresponding place and strum it with one of your remaining fingers.

But what about the squealies?

In electric guitar playing, we are most interested in a slightly different kind of flageolet, known as (artificial) pinch harmonics, or "squealies", in tablature, they're marked PH. These are the squeaky or wailing sounds you might mostly know from metal solos, where entire passages are often played this way. But they are also used by many guitarists in other genres, especially when they want to add extra punch and energy to the tone.

I should add that another way to achieve the squealies is to tap the string with your right hand at the point where you would play artificial harmonics – as you would when using the tapping technique. This is called Tapped Harmonics, or TH for short.

The difference from a normal tone played with a pick is abysmal – especially if you back up the squealing tone with a vibrato or pluck. Suddenly, the guitar comes alive, turning into a wild animal you can barely keep "on the chain". When you spice up your solo with a few flageolet notes, it's as if you're in control of a huge amount of energy that occasionally bubbles to the surface. It's similar to singers controlling their voice for most of the song and then giving it their all in the final chorus. You're working with anticipation, tension and a release of energy.

Like learning to whistle

Do you remember when you learned to whistle? A lot of people will tell you how to do it – you have to pucker your mouth like this, and, well, you blow, and that's it! You pucker, you blow... and nothing. Nothing for a long time and the frustration grows. And then, one day, IT comes! From that moment on, you can whistle.

Playing the squealies is very similar. Check out the videos on YouTube. Ask a guitarist friend to show you. And then try it. It might take a while, but you'll get the hang of it. There's another funny thing about playing flageolets, though – sometimes they occur spontaneously, but you usually don't know when and can't reproduce it. Learning to really control the whistling – to get the flageolet to sound the right way and at the right moment – is a very long haul, even for advanced guitarists.

Here's some advice to get you started:

- You'll do much better with distorted sound, don't be afraid to crank the overdrive to the max. If you have an effect that increases the sustain of the instrument, you can add it. My experience is that a pickup near the bridge works better, as it generally absorbs more feedback and all sorts of noise. Also, a humbucker is better than a single. And when you get flageolet to resonate, play a very dynamic wide vibrato with your left hand.

- Of course, the most important thing is the pick strike... Hide it between your thumb and index finger so that only the tip is exposed, rotate it so that it is at about a 45° angle to the string, strum and immediately touch the string gently with the side edge of your thumb in one motion. The strike with the pick should be vigorous, not in the sense of force, but rather in terms of "attitude". In short, don't be afraid of it. Also, try different positions between the bridge and the pickup at the fingerboard, in some positions – different ones for different notes – the string is more willing to squeal.

How to continue working with string harmonics?

If you want to improve at playing the "squealies" and especially gain control over when and how they sound, pick a riff, solo or lick from your favourite guitarist and try to learn it as accurately as possible. Make the flageolets sound where they're supposed to, every time, if possible. It'll probably take you longer than you think. But you'll be all the more pleased when you get it right. It doesn't matter if you gravitate more towards metal, rock or blues, like vibrato, squealies form part of most guitar masters' sound.

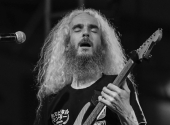

At the same time, everyone uses them a little differently. From Jeff Beck's subtle accents to the energetic moments in David Gilmour's solos or Zakk Wylde's gritty rock riffs, to Joe Satriani's wild wailing tones and Steve Vai's otherworldly sounds. The more positions you try out and practice, the more possibilities open up for you to use pinch harmonics in your solos. And a certain unpredictability of what will actually "come out" of the squealing tone is just part of your guitar adventure.

What is your experience with playing the squealies? And which kind of flageolet do you use most often? Let us know in the comments!

If you have found an error or typo in the article, please let us know by e-mail info@insounder.org.