10 Tips for Your First DIY Musical Bicycle Tour

What’s more “folk” than going on tour by bicycle? In my previous article, I shared my own experiences of this summer’s musical bicycle tour with Czech chansonnier Jan Řepka’s “Bicycle Band.” Are you thinking about planning a musical bike tour of your own? Then I have some advice that might come in handy….

1. Take control over your health & dare to be boring

For the love of everything holy, if you have a chance to order your own food, get the salad and not the burger with extra bacon and a side of French fries. If your budget doesn’t allow staying in a hotel every night—which was our case—and you depend on friends and bookers for providing you with room and board, it is very likely that you will be confronted with large quantities of greasy food and alcohol and will be asked to jam throughout the night. As fun as that may seem (rock ‘n’ roll!!), if you wake up with a hangover the next morning, you can’t just have someone drive you to the next gig while you sleep it off in the back. No-one is going to haul your bloated body on the back of their bike. But even if you don’t drink alcohol, a compromised immune system or exhaustion can put your tour in danger. You don’t want to get the flu or lose your voice. In our case, three quarters of the band got a bad stomach virus that made us feel miserable for three days: vomiting, not being able to eat, fatigue, excruciating headaches, fever… And yet, we still got on the bike and onto the stage (rock ‘n’ roll… Thanks, painkillers!). Canceling a gig and staying in bed was not an option, as it would mean having to cross twice the distance the next day.

Yes, it feels bad to refuse food that someone lovingly prepared for you, or a shot of someone’s finest moonshine they pull out for a toast in your honor, or to go to sleep early when they expected this to turn into a wild night to always remember. But as long as you’re not Keith Richards, you will need to set some boundaries for the sake of your health and professionalism. Repeatedly.

2. Have a good rider and make sure it’s understood

What do you think of when you hear the word “Rider”? My guess is that you’re either thinking of a technical rider (verbal commentary on the stage plan) or of blue M&M’s and other ridiculous demands. Many musicians just can’t think of what to put in a touring rider, because they think that their needs and expectations should be obvious. Well, if you’re the type that can sleep anywhere at any time, live on a diet consisting solely of sausages and beer, and if “sweaty/grungy” is your stage dress code, and if you don’t mind playing for an empty room or having to cycle 50k extra because of a cancellation or location change, then you’re right—no need for a touring rider and congrats for being a true hippie nomad!

For the rest of us mortals, in order to avoid the dramas described under item #1 and to guarantee consistently professional shows, it’s not a ridiculous luxury to ask your bookers / hosts for these things:

- Healthy food (you can even specify this or give some examples of what you like to eat, for example: yoghurt with muesli for breakfast, a salad for lunch/dinner…)

- Clean drinking water

- A quiet place to sleep

- A shower (not a luxury after biking all day during a heatwave)

- A private space: for rehearsing, warming up or just concentrating

- A safe place (that can be locked) to store the bicycles and personal belongings

- A place to sell merchandise

- Cooperation in promoting the gig, such as putting up posters

- A plan B in case it rains (covered stage, moving indoors?)

- In case the show is outdoors after dark: stage lighting

- Occasionally: access to a printer

- Occasionally: access to a washing machine

Communicate with the booker / host and make sure they have understood and accepted your terms.

3. Every kilo counts

Obviously, the lighter the load, the easier you will pedal or push your bike uphill. When packing your sleeping bag, clothes, first aid kit, and tools, carefully consider what you really need and whether there are lightweight options. Don’t pack too many clothes or food: you can have your clothes washed and you can stop at a grocery store daily, assuming you’re not planning a musical bicycle tour through the desert or the North Pole.

We were completely self-sufficient in amplifying our concert for intimate events (20-70 people), ideally in the open air. Basic criteria: quality, weight, size, durability, simplicity. The AKG condenser microphone allows us to amplify our three-part harmonies naturally without having to carry triple the equipment. The small AER combo supplies the microphone with the necessary phantom power. Plus, only one microphone stand is needed on stage. The only downside is the greater susceptibility to feedback. For larger concerts or acoustically more demanding venues we agreed with the booker that they provide an adequate PA system and sound engineer.

Our gear:

- AER Alpha (combo used for guitar, voice and violin)

- VOX VX50-BA (bass combo)

- Behringer MX400 (mini mixer)

- AKG C2000 B (condenser microphone)

- Larson Stetson Style 2 VS1900 (guitar) with built-in pickup

- Kala U-Bass Mahagoni FL (bass ukulele) with built-in pickup

- Akord-Kvint Jan Lorenz (concert violin) with Fishman V-100 piezo pickup

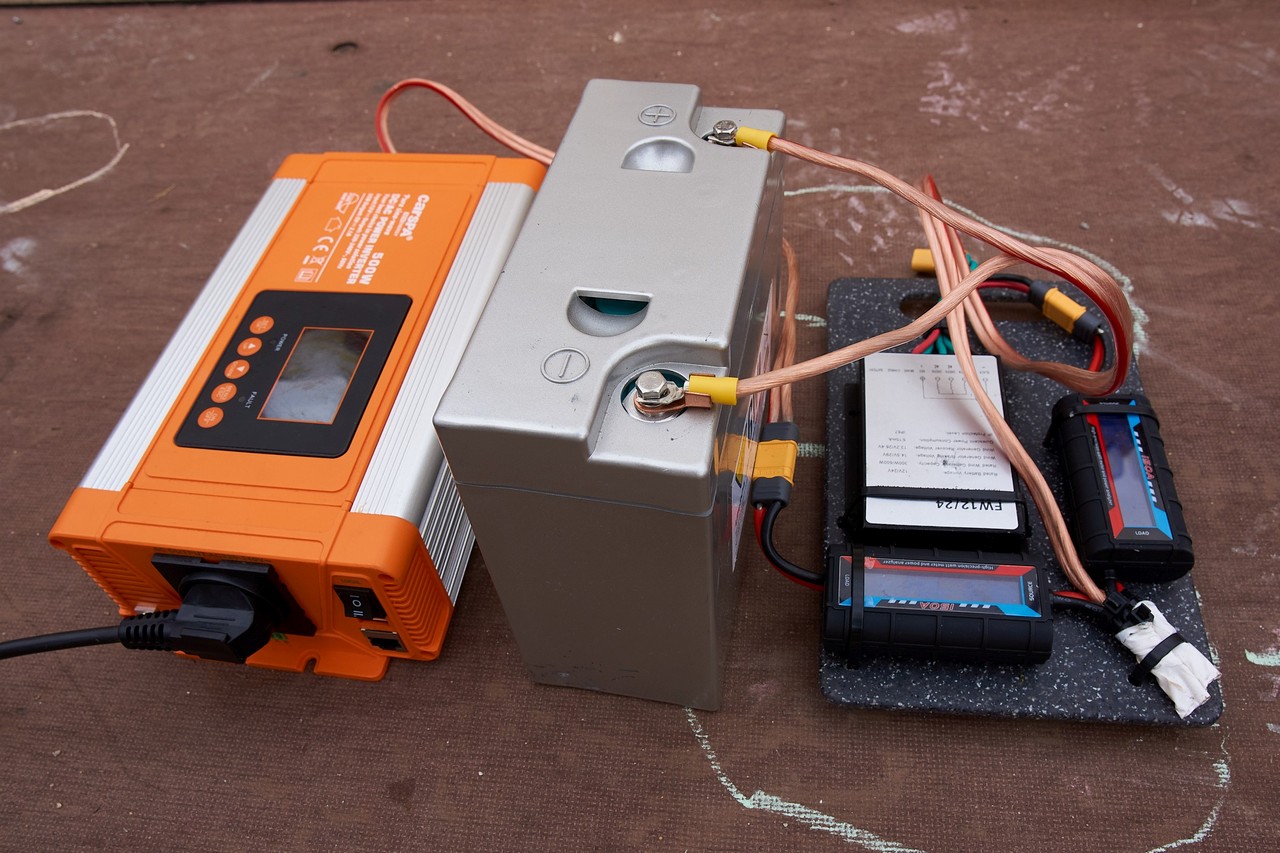

- LiFePO4 12V 20Ah battery and 230V AC inverter with sine wave output. Average consumption during busking was less than 50W, so the battery lasts for about 5 hours of playing.

- Plus three boxes of CDs, 100 printed programs, cables, one mic stand, instrument stands and two other bottomless boxes full of small essentials.

4. Pack functional clothing and some nifty tools

Be prepared for all kinds of weather. It’s gonna be hot, it’s gonna be cold, it’s gonna rain, and you’re still gonna get on your bike and go. Pack water-resistant clothing and/or materials that dry quickly. Don’t leave anything outside overnight as it might rain. Pack lights and reflectors for if you have to bike to the hotel after a gig in the dark. Wear a helmet and some protective gear. Have water nearby at all times. Be careful with the sun: apply sunscreen and stay in the shade. And of course all musicians already know that Gaffa/Duct tape is absolutely essential for fixing pretty much anything.

5. Communication & Compromises

Do you prefer sleeping in and lazy mornings, even if that means cycling in the hottest part of the day? Or would you rather get up early, cycle when it’s still a bit cooler, and arrange a siesta later in the day? Which meal is most important to you: breakfast, lunch, or dinner? What happens when you get “hangry” or don’t get your morning coffee? What time do you need to go to sleep? What are your pre-concert rituals that you need to stick to in order to give a good show? On tour, your band is your family, and you don’t want to have to entertain a crowd right after having a big family fight. Talk about these things, defend what is really important to you, but also be ready to make compromises.

6. Make new friends & keep the old

A tour is an excellent opportunity to organically expand your fanbase. You can collect new contacts by passing around a sign-up sheet for your newsletter at gigs or having a guestbook. There are all sorts of ways to make sure people know where to find your website or social pages: a banner, a QR code, business cards, you name it. We chose to hand out a printed program with our contacts, some background information about the tour, and lyrics to the choruses of a few songs so people could sing along.

Personal contact is still the most effective way of promotion, so if you can somehow keep track of where your (old and new) fans and friends live, you can reach out to them directly when you are playing in their area. General posts on Facebook can still be good for something, though: if your tour is in the summer, people might be on holiday exactly in the area where you are gigging, and a friend from Prague might surprise you by showing up to a concert on the other side of the country.

It can also be useful to have some emergency contacts: someone might be willing to deliver an extra supply of merch if you’re sold out halfway through the tour, provide you with room & board, organize a house concert, or help fix your bike.

7. Divide (tasks) and conquer

Don’t all of us musicians dream of having a manager and a crew of roadies, so that we can focus on performing only? We were very lucky to have a fourth, non-playing person come along on our tour who was able to relieve us of part of the burden: he takes amazing pictures (don’t underestimate the importance of visually attractive documentation of your tour!) and also took on the roles of navigator (planning the route so that we avoided heavy traffic, unnecessary uphill climbs, and rough terrain) and mechanic (providing battery power when we went busking and fixing some minor bicycle breakdowns) as well as helping setting up and manning the merch table, passing around printed programs to the audience, and collecting money in case we were playing “for the hat.” Sometimes he went to a grocery store while we were playing to buy us some food. If you can’t find such an all-round non-playing member to accompany you on tour, bear in mind that all these tasks will fall on you as musicians, and you already have a lot going on. Don’t automatically assume that the band leader will take care of everything: they are most likely the one who has already done most of the work in preparing the tour and they have the largest responsibility on stage for entertaining the audience. Divide tasks fairly so that nobody gets a mental breakdown from either being overloaded or bored to death.

8. Easy does it

So you’re an avid cyclist, you normally zoom uphill really fast and are used to traveling distances of over 100k per day? Good for you! But a musical bike tour is not quite the same as a sports vacation. You have gigs to play and you have to be consistent—it would be stupid to burn all your energy on your bike if that means you can’t stand on your legs during your evening concert.

In 10 years of experience, Jan Řepka found that 50 kilometers is a good daily maximum. Most days we traveled only 20-30 km. Sometimes that felt a bit unsatisfying, but on those days when we were ill (see item #1), we were thankful that he had planned it that way. Also, it gave us a lot of time for rehearsals, socializing with our hosts, mentally preparing for concerts, fix a mechanical problem, and even some time off to go swimming or read a book.

If you are used to going uphill as fast as you can just to get it over with, you might want to reconsider this when lugging a load of about 60kg. You might be proud of yourself for conquering that first hill, your heart beating at techno pace, but there will be another hill. And another. And another. Why rush?

Even going downhill you should be careful: a heavily loaded extended cargo bike is hard to steer. If you’re going downhill at breakneck speed and there’s a bend in the road, you might not be able to handle the bike on time—and you could fly off the road or crash into an approaching car. It would be a waste of the energy you put into booking concerts if you have to cancel them because you’re in the hospital or dead.

9. Know thy weaknesses (and strengths)

We played all kinds of concerts: from busking on the streets and subsequently suffering from sunstroke, playing in a pub where the regulars who were talking loudly and smoking cigarettes for most of our concert until they had to go home to put their chickens in the coop, under a romantically lit birch tree at a garden concert, to the main stage of a large festivals for hundreds of people who listened attentively. And though our “main protagonist” Jan Řepka is perfectly capable of giving a great performance at any of these occasions, he knows himself and his repertoire well enough to know exactly what works and what doesn’t. He knows that he gets distracted when people in the audience talk, and that means he will skip certain songs and will not devote as much attention to introducing the songs with a story—which is a real pity, because it is one of the things that make his shows so interesting. He also knows that is it very demotivating to play for fewer than 20 people (unless it’s a house / living room / garden concert for a select group of people in return for room & board). And he knows that the amount of work he has put into his show and that this is worth a fair compensation.

So in booking the tour, these were our 3 golden rules:

1. Audience: The booker needs to guarantee a minimum of X people

2. We need to be paid a minimum of X

3. We provide a concert, not “musical wallpaper”: there should be no disturbances

We made a few exceptions when one of the three rules could not be met, but we still had a good reason to want to do that particular gig.

10. Remember why you’re doing this

During the process of preparing and booking a tour, and during the tour itself, everybody involved will have one or several smaller or larger crises. You will get tired or frustrated and wonder: why am I here? Why do I pour out my heart and soul to these people who don’t even bother listening to me? Why do I keep planning tours if only 20 people come to my gigs while other musicians fill stadiums easily? Why didn’t I just stay at home, take the car, have a normal office job like everybody else? Whoa Nelly, back up there. Go back to that moment that you decided to be a musician. Go back to that moment you decided that a bike tour would be a cool idea. Go back to that concert when you thought nobody gave a damn, because you were focusing on that table of people talking and playing cards—remember the couple sitting at the table next to them, who were smiling at you all the time and came up to you after the show to tell you that you made their day? Remember that little kid who wanted to have a go at your instrument, got really excited about it, and might become a musician themselves some day? Remember the grey-haired, retired musician who shared interesting anecdotes with you and sang you songs that you would normally only find in a dusty archive, this living cultural history?

If you’re traveling with a band, remember that you are not alone—your band mates will help you through rough days and you will do the same for them when they are feeling low. If you’re traveling solo, remember that being alone does not equal being lonely—and that you should enjoy being able to make all your own (logistical as well as musical) decisions, because you will soon return to “normal life” with plenty of people breathing down your necks. Remind yourself and each other of these positive points, don’t give up, and enjoy it while it lasts.

If you have found an error or typo in the article, please let us know by e-mail info@insounder.org.