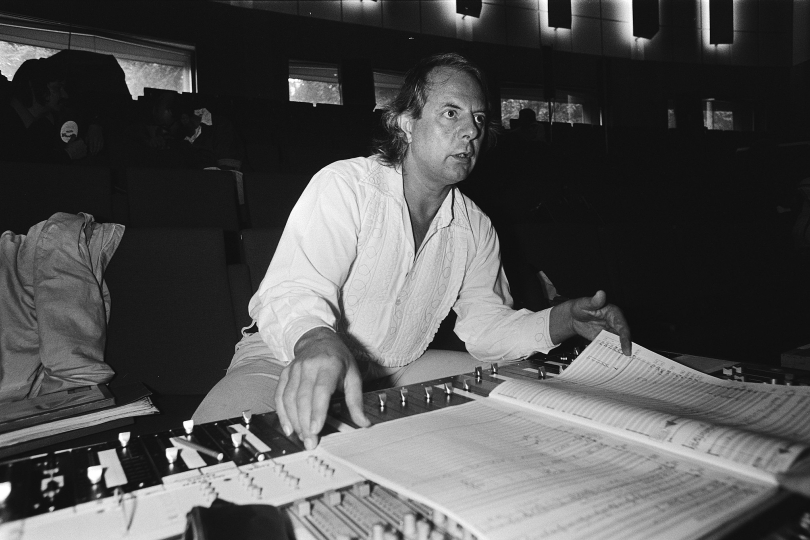

Milestones in Music History #24: Karlheinz Stockhausen, The Visionary

The path of sound experimentation carried out by Raymond Scott, protagonist of our previous episode, was not a single sparkling and fleeting comet. The approach to the concept of sound and music in a scientific way, the study of the movements of sound waves and the possibility of manipulating the wave frequencies gave the artist almost infinite possibilities of expression. With the spread of synths and sequences, not only did the way of producing music change, but also the way of thinking about music. Research on sound explored new and controversial universes, and the transition from music composed in a traditional way to music that admits errors would have only been possible thanks to a pioneer and a daredevil who, coming from the canonical knowledge of sound, arrived at a new compositional theory. Only one man could have opened the doors to the world of contemporary electronic music.

Despite having completed classical studies in musicology and musical composition, Karlheinz Stockhausen did not immediately attempt to compose and began to nurture his first real interest in composition in 1950. It was only during his third year at the conservatory that Stockhausen began his musical production and during this period he had the good fortune to meet some composers who were decisive for his artistic growth: Frank Martin, a Swiss composer whose lectures Karlheinz took in Cologne at the end of 1950; Karel Goeyvaerts, a Belgian composer who had studied in Paris with the masters Olivier Messiaen; and Darius Milhaud, whom he had met at Darmstädter Ferienkurse, a summer event of contemporary classical music.

Stockhausen also wanted to follow Goeyvaerts' example, so he relied on the didactic guidance of his own masters in Paris and later left the city in 1953 to become Herbert Eimert's assistant at the Electronic Music Studio of Nordwestdeutscher Rundfunk, where he would become director only ten years later. In the years preceding his direction, he continued to study music theory and worked as an editor at the scientific music journal Die Reihe. Together with his academic activity as a teacher and researcher, he began his experimentation in the musical field.

Already following his visit to the Darmstädter Ferienkurse, he had begun to develop his first compositions and to work with athematic serial composition, in objection to the dodecaphonic theory put forward by Arnold Schoenberg. Serialism in music - that is, composition using a series of pitches, rhythms, dynamics, timbres or other musical elements - began with Schoenberg. But the principle applied by Schoenberg and supported using a twelve-tone system, returned a harmonic and melodious composition, in which none of the notes were prevalent, but the fluid sound of the twelve-tone scale resulted in an organic and composite music.

Serialism was already perceived by Schoenberg's contemporaries as an expression of atonal or post-tonal music, a true revolution of sound, where harmony was not achieved starting from a single note and then developed into a twelve-tone scale starting from that note, but rather the sound developed from loose notes. Schoenberg had already made atonal compositions, particularly from 1908 to 1923 (notably, the Pierrot Lunaire of 1912). However, his atonality always remained in some way bound by a single key element, which almost performed a "pivotal" function around which his musical harmony revolved, even randomly.

Stockhausen started from Schoenberg but returned to serialism and atonality, highlighting the ability of music to be casual, to be able to experiment on sound without following established rules - in short, to dare. His first compositions are defined by himself as punktuelle Musik - that is, "punctual" or "pointist" music - that consists of independent parts, single sound forms that are part of a group but do not reflect a uniform vision.

The punctuality emphasised the "personality" of the single notes, rather than creating a system where the notes are "bricks" of a musical ensemble. Not only that, but each note had distinctive and independent characteristics from the other notes and from the composition in general. This system is applied by Stockhausen in some of his early compositions, such as "Klavierstück IV” - the fourth part of a series of compositions defined by the musician as his drawings and this last part cited by himself as an example of punctualism – as well as Kreuzspiel and the first unpublished versions of Punkte and Kontra-Punkte.

Punctualism was Stockhausen's first real step towards electronic experimentation. Shortly thereafter, within a few months, in December 1952, he was lucky enough to visit the amazing musique concrète studio of Pierre Schaeffer in Paris, where he composed his Konkrete Etüde. A couple of months later, he moved to Cologne, where he officially made his debut in electronic music and in 1953 and 1954 he composed his two Electronic Studies.

Apart from being the first published score of electronic music, his Electronic Studies reflect a mature and almost contemporary approach to music. He did not want to use acoustic or "concrete" sounds in his compositions, but only made use of pure sounds emanating from a frequency generator - each sound on its own, deepened and enhanced, as an independent cell, which exists alone without the help of another.

In 1955-56 he composed and published another electronic music piece, with some concrète parts, his Gesang der Jünglinge. Meanwhile, his personal music theory also shifted, as he recognised that timbres couldn't be conceived as a standalone entity, but take part in a more homogenous group composition. But he also realised that the focus in his compositions should not be centred towards a single tone, but rather on the direction and movement of the composition.

In fact, he established new criteria for music composition, putting emphasis on randomness and on the possibility that sound could be produced and propagated without a certain direction. The focus on the aleatoric aspect of music was very revolutionary, as it completely changed the artist's approach to the composition. If music is left to chance, possibilities for the evolution and "behaviour" of sound are infinite.

Not only that, but Stockhausen also focused on the musical variables - for example, the performer's skills and the environment in which the music is performed - all factors that can determine some features of a composition. He also showed how a music piece can be presented in other forms, as in the case of Zyklus, where he began to use graphic notation, which started to be in vogue right in the 50s - it is closely connected with aleatoric and experimental music (and of course with visual arts) and in this context, it is often almost impossible to follow regular music notation.

Still, in these years, Stockhausen developed the concept of music spatialisation, where there is a specific and designed ad hoc context where a certain composition was to be performed. He himself described this as "a spherical space which is fitted all around with loudspeakers. In the middle of this spherical space a sound-permeable, transparent platform would be suspended for the listeners. They could hear music composed for such standardised spaces coming from above, from below and from all points of the compass."

Even though the real music revolution that he ignited happened during the 50s, his work continued and evolved until our days. He was a tireless and very productive artist and until the night before his death, which happened on the morning of the 5th of December 2007, he worked on finishing a commissioned work for performance by the Mozart Orchestra of Bologna.

The legacy he handed to us is priceless: his Studie II is probably his most representative work, and it became a milestone of his career, as well as in the history of electronic music. Obviously, he greatly influenced the music of the 50s and 60s, particularly the work of the Polish composers Andrzej Dobrowolski and Włodzimierz Kotoński, and the famous Italian composer Franco Evangelisti.

But such a visionary figure could not reappear in our days: Frank Zappa acknowledged him in the notes of his 1966 album Freak Out! and artists like Miles Davis, The Who, The Beatles, Pink Floyd and more recently Björk acknowledge him as an influence. Someone like Kraftwerk and Irmin Schmidt and Holger Czukay (both founding members of the experimental band Can) had the fortune to study with the visionary sound master. One student probably distinguished himself for his special skills and he's going to be the protagonist of our next episode of Milestones. We are talking about Jean-Michel Jarre.

What was Stockhausen's intuition? Is aleatoric music a system only applicable to experimental music? How can randomness cope with performance repetition? Is it possible to apply a fixed canon to experimental electronic music? Will Stockhausen's work be still impacting in the centuries to come?

Leave us your opinion below in the comments!

If you have found an error or typo in the article, please let us know by e-mail info@insounder.org.