Milestones in Music History #41: Morton Subotnick, The Innovator

The plunge into the wild experimentation of Godspeed You! Black Emperor, the protagonist of our previous episode, took us to the edge of contemporary experimental music. A multifaceted and complex universe, which, like all things has its origin. In fact, we must turn our gaze to sunny California and back to the 60s, to find who could be called the godfather of electronic, experimental and techno music. The genius Morton Subotnick.

How much would we like our musical compositions to become an essential historical point of music? This desire responds to the human will to surpass oneself and to change for the better. Not only that, we would also like our product to be a breakthrough between eras and music genres. And maybe, if possible, give another function to the musical instrument, freeing it from the canonical approach and giving it a new life.

The ability to combine all these elements belongs to a brilliant and innovative mind. Morton Subotnick was born in Los Angeles and graduated from Denver University. He started composing music very early and in 1962, he founded the San Francisco Tape Music Center together with the composer, visual artist and writer Ramon Sender.

It was a non-profit corporation supported by musicians and composers who handled tape recorders and other electronic equipment and functioned as both a concert venue and an electronic music studio. In the same period, he collaborated on two works by Anna Halprin. The move that changed his career, however, was his appointment as music director of the Actors Workshop, which led him to move to New York, where he became the first music director of the Vivian Beaumont Theater.

Meanwhile, the Tisch School of the Arts had recently opened in the city, and Subotnick became artist-in-residence here (together with New Zealand director Len Nye, best known for his experimental works and kinetic sculpture) and was entrusted with a studio and a Buchla synthesizer. Buchla & Associates was founded in 1963 by Don Buchla – one of the pioneers of the synthesizer – in Berkeley, California.

The company's first product, the Buchla 100 series, was commissioned by the San Francisco Tape Music Center (yes, that's right, by Ramon Sender and Subotnick himself), who later provided a $500 grant to Buchla to produce the instrument. It was a sensational electronic machine, as it replaced musique concrète-style sound generation, providing specific functions for sound composition, such as sequencer modules, oscillators, envelopes, filters and controlled amplifiers.

The system involved a touch pressure response from the composer, who then modified the pitch, timbre, spatial location and amplitude of the sound. In short, a little gem. In New York Subotnick also became artistic director of the Electric Circus and the Electric Ear, which he had helped in its gestation.

It was in those years that he began working on his first real musical production. In the 1960s, experimental electronic avant-garde music was based on very minimalistic musical compositions, which included pitch and timbre changes, but no musical sequences and even fewer rhythms. These were individual sounds in their own right, not tied to a pattern. And that was the Subotnick revolution. He was the first to introduce the concept of rhythmic sequence, beats, pulses and sequential melody.

And so in 1967 his debut album, Silver Apples of the Moon, was released. The album contains the composition that gives the album its name, divided into two parts. Subotnick took the album's name from a poem by Yeats, "The Song of Wandering Aengus". The composer's goal was to create sounds that would be difficult or impossible for another musician to recreate.

He made use of his Buchla 100 for the most part, and two tape recorders, one that recorded and played back and the other that functioned exclusively for playback. He explored the full potential of Buchla, creating melodic and rhythmic sequences, which he then applied to tape recordings. Subotnick produced the album in sections, to work on different patches and then play with them, with overlays and redundant effects

The result was an experiment that winked at minimal electronic music, enriching it and making it more usable at the same time. He also used noise, typical of the avant-garde, through the sound of sirens, glissandi, whistles and other ambient noises. Finally, the improvisational vein of the whole album was quite apparent, a very different approach compared to his predecessors of experimental electronic music.

The combination of experimentation and metrics was successful, giving a musical product that even Subotnick couldn't predict – he had left some compositional sections to chance, not knowing what the result would be. The album has been considered by some as a forerunner of disco dance music and in it you can see the first developments of techno music.

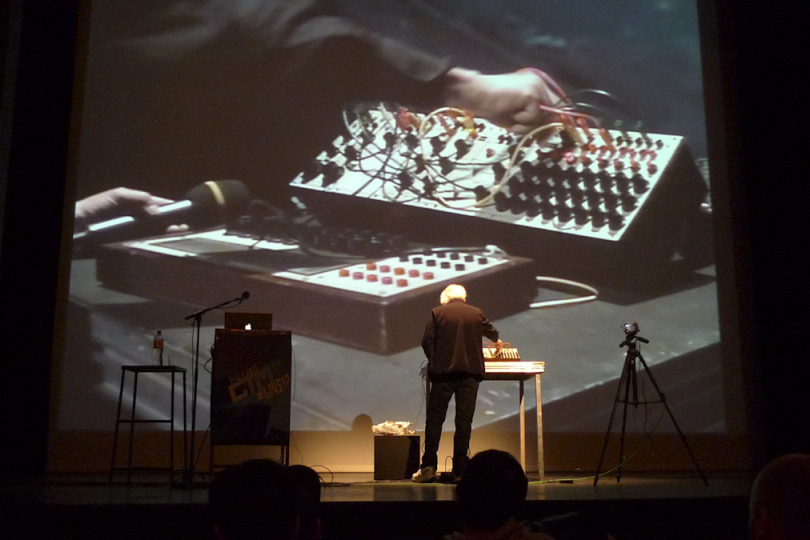

With his second work, The Wild Bull released the following year, Subotnick confirmed that the revolution in the field of experimental electronics had already begun. His production continued over the years, doing commissioned works and collaborating for theatrical pieces and other multimedia and in recent years he began to use computer sound generators for his compositions, an intelligent and interactive system with which the performers could interact with the artistic product itself.

Another great revolution by Subotnick, even if it all was born from his first two works, which represented the keystone of contemporary experimental music. The legacy of Morton Subotnick is indescribable – he is still alive and well, and musically active – one of his latest creations is Subotnick's Pitch Painter for iPad and iPhone, a touch-and-draw music app that allows children to create music intuitively, using digital touch.

Subotnick's real revolution was his different approach to musical composition and his intuition of relying on improvisation, but with the help of sequencer and rhythmic bases and incorporating experimentation and noise. From him started the innovation that led to the birth of techno and the development of dance music of the 80s.

As a teacher, he had many students of worthy fame such as Rhys Chatham, Mark Coniglio, Charlemagne Palestine, Lois V. Vierk and John King, but I believe that we all learned a little from his innovations. Another musical genius who contributed greatly, like him, to the transformation of composition, focusing on aesthetics and music theory, was Tōru Takemitsu, the protagonist of our next episode of Milestones.

How can musical composition be improvisation and metrics at the same time? Are electronics a man-made product, or is man gradually being replaced by machines? Can the computer be considered a musical instrument? And what are the limits of improvisation and experimentation in the contemporary era?

Leave your opinion in the comments below!

If you have found an error or typo in the article, please let us know by e-mail info@insounder.org.