Tony Buck: Drum Kit Is like a Kaleidoscope

Tony Buck is a rare natural phenomenon among drummers – like an aurora, his creative way of playing is unpredictable, ephemeral and elusive. At the age of 62, he keeps on developing it, experimenting, discovering innovative techniques, searching for new sounds and pushing the boundaries beyond all concepts of how the drum kit should be played. He is best known around the world as a member of the trio The Necks, he formed bands such as Peril, Spill and Weird Weapons and he also runs the solo projects Unearth and Environmental Studies, one-man-band performances for which he makes his own percussive devices. He also collaborated with numerous artists, among them John Zorn, Lee Ranaldo from Sonic Youth, The EX, Christian Fennesz, Han Bennink and Ground Zero. We talked about his musical evolution, the bright and dark sides of drummer's life, how to break free from the rut of the groove and the role of the band's metronome.

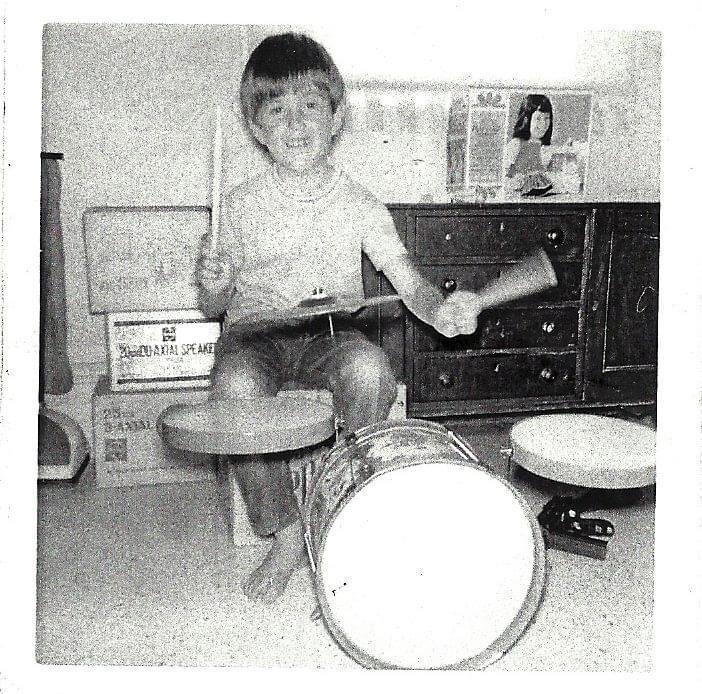

My first musical memory is smashing pots and pillows until my mom got upset and my dad bought me my first drum. Where did your musical journey start – can you trace any early childhood memories of important moments which drew you towards making music?

I used to hit pots, pans and pillows too and I remember my mother had an ironing board with a metal grid on it, and it really sounded like a snare drum. I loved playing on that. But I think even earlier when I was five or six, I was given a small drum kit by my parents and I guess I just really took to it. It was really a toy, so I played it for a while and I probably outgrew it. I had some lessons in marching drum in primary school. I really just liked the feeling of playing the drum. Quite early I sort of had the thought that this is what I wanted to do for a living. I started to take lessons very seriously when I was about thirteen. And then, I guess because of my desire to do it well, I started looking into how jazz players played because it seemed like the most advanced use of the instrument. More than being drawn to that music specifically, it was rather about playing the drums well.

Were your parents involved in music?

Not at all. We didn't even have a record player in the house when they bought me the first drum kit. They weren't into music at all. We got a record player when I was seven or so and my parents would buy records like James Last, Burt Kaempfert and stuff – the kind of background, easy-listening music, that was popular with people for whom music didn't mean that much, I guess. They did however give me three records for Christmas: Hard Days Night by The Beatles, an album by Glenn Campbell (singer and country guitar player) and a soundtrack for a Disney film.

How did your first bands influence the evolution of your way of playing?

In school and after school, I was playing in rock bands, later in jazz bands and slowly getting into the idea of improvising. So it was sort of a continual evolution, I guess. A straight line through trying to accumulate more knowledge and different approaches and ways to use my imagination with the instrument. And playing these different styles in parallel – I never stopped playing rock music the more I got into jazz and improvised music – I liked to cross reference one with the other. For the last decade or two, I've been concentrating on my own way of playing music, which does tend to move towards free and abstract improvisation.

30 years in 3.5 minutes – timelapse of Tony's playing style development. Starting at 1:30 you can see his DIY percussive devices.

I know you can play other instruments too so what is it that makes a drum kit the most magnetizing one for you?

I really like the feel of playing drums – the tactile, haptic response I get from the instrument. I also like the idea of a broad range of timbers, different tone colours. Very early, as a kid, I used to write pop songs and I learned to play fundamental guitar chords with which to write these songs, and at that time, teachers would say to me: "If you want to do that you should learn to play the piano." I really wasn't interested – I was quite interested in learning the mechanics of music like harmony and so on but only as much as I had to – to use it as a tool. I just wanted to play drums really well. I don't know why really. It seems freer to me without the restrictions of working with harmony, having to be in tune and the key and so on. I also like the fact that it is such a colourful instrument, from all the shimmering metal sounds to the warm drum sounds. I remember, because I was into playing percussion, it was suggested to me that I could perhaps learn to play vibraphone or so, but that for me, at the time, was such a monochromatic instrument with just one tone colour and I would get bored with the sound very quickly. But I never felt like that with the drums. The drumkit is like a kaleidoscope.

That's a beautiful metaphor! I love that about drums too but let's talk also about the dark side of playing the drum kit. I have quite a lot of drummer friends who have suffered from health issues such as tinnitus, piles or back pain because of long sitting and wrong posture, while not even playing in such an extreme way as in the movie Whiplash. How did you manage to stay healthy while playing for decades?

That's an interesting topic – there are issues that drummers get like carpal tunnel syndrome or RSI (Repetitive strain injury) which I had hints of when I was about seventeen and I was touring with a rock band while studying at the conservatory. It was the first time I was playing in a proper rock band in big venues and I think I played way too hard. I started to have a sense of developing RSI but there was a chiropractor in the band and he told me how to break up these cohesions which develop in the tunnels where your tendons move. I did it and I haven't had a problem since, even playing really repetitive music with The Necks, I don't get any tension or repetitive strain issues anymore.

And what about your back? It seems that you're able to keep a good posture while playing.

Well, when I was about fourteen I developed scoliosis and then had an operation on my back and my spine is actually fused together – I have a steel rod in my back so the whole centre of my back is solid and I can’t actually bend my back now. I was really into playing drums and I was told, "You can't play for six months," which is a really long time at that age. But then I used the time to develop other things like working on hand coordination while just sitting on a chair. I don't know how this has affected me while playing drums – in a way, I look like I have a good posture since I sit so upright but that's because I can't bend. So maybe that's been helpful in a strange way, but I don't really know how it affected me one way or the other, negatively or positively, because I don't have the option to compare of course. It is what it is!

Learning to play drums seems to me rather a way of unlearning – especially the movement stereotypes, limb coordination patterns and so on. Once I told Steve Reich that often, while playing drum kit, I felt stuck in these patterns and asked him how to get rid of them. He replied: "Of course, because the drum kit is a trap! You need to experiment and move things around – if you're right-handed, put your ride cymbal on the left and hi-hat on the right side."

When I watch you playing you seem to be able to get out of the trap while keeping the classical drumkit setting. How did you manage to do that?

You never really manage but you try to develop a way to control an independent voice with your different limbs and different sound sources. Rather than thinking about your body and its limitations you think about the sounds you want to make and how to achieve what you hear in your head.

Interesting, so you're suggesting it's rather a question of directing one's attention within the creative process?

Indeed, you're aiming for the sound, not for the physical movement to make the sound. It's interesting – there are a lot of theories about the drum kit because it basically replaces the role or function of a lot of people – it makes one person able to do the job of three. And I know a lot of people who think that the development of the bass drum pedal, for example, meant that you wouldn't need a "bass drummer" and that one person could play that role at the same time as being the snare drum player, that's where the idea of being "tight" developed – so you could actually coordinate things really tight so it's not like two people trying to do something together but one person – in total coordination or agreement if you like – if one person does it, you know you can be right on. And the idea is that the sense of a "tight groove" developed because of that. But other people think that you lose the sense of organic relationships because it's too tight and that a group of musicians playing together is actually much more groovy and "feels" better than just one person doing it alone.

That brings my mind back to Steeve Reich and his polyrhythm phasing technique, which is based on this phenomenon.

Yes, that is why African drum ensembles (source of S. Reich's inspiration, ed.) sound much more organic and flowing than just one person doing the same thing on a drum kit. That's also why, as you say, people seem to think I play in a way that sounds like two people playing because I am interested in the idea that separate parts don't coordinate so much, but ebb and flow. And I like the idea that different levels of rhythm operate in different spaces within the rhytmic and timbral bandwidth, playing something in the space where something else isn't happening at the time. Standard drum kit independence is all about playing within a grid, that you coordinate. You're sort of able to do things independently but they always relate to one another, so they are not really independent at all.

So how can one attain real independence?

The sense of real independence is just a different skill to develop for a lot of musicians, not just drummers – piano players often play something strong with their left hand while playing a flowing melody, sometimes quite rubato, with their right hand.

So is that how you managed to get out of the trap?

Yes, actually it's not such a radical idea! And regarding the trap (and that kind of language), drummers often talk about playing in the groove but another way of looking at it is that a groove is also another word for a rut. And who wants to be in a rut? Also, they talk about being really "tight" or being "in the pocket". Those terms are meant as positive regarding playing drums or with a band – "the band was really tight". But being

tight is the opposite of being free. Why would you want to be all tight and tied up and in a cage? You want to be free, open and loose. So I think the language is quite interesting. I mean, I love music with a groove as much as the next person but what I suggest here and within my way of playing is that there are alternatives to that.

Another aspect of getting stuck while playing in a band is the expectation of many musicians that the drummer should be kind of a living metronome – responsible for keeping the tempo. Billy Martin once told me that every musician should keep the tempo, which will enable the drummer or percussionist to become really creative.

Well, more often than not that's the expected function of the drummer, isn't it? But even in a broader musical sense, I don't really see why, if everyone is playing on the same grid or tempo, it has to be stated like a click track or a metronome anyway. So yeah, it is everybody's responsibility to keep the tempo. I don't know why all music has to be referenced against the grid and if it does, why it has to be stated like a graph paper over which the other musicians do their thing. To me, that seems like holding on to the training wheels to keep the bike steady. If musicians need the drummer to keep the beat for them then I would suggest that they have deficiencies in their own internal timekeeping.

Amen. From this point of view, how was your experience in the bands you've played with?

I remember playing in a group with an amazing saxophone player from Australia, Mark Simmonds, who was strongly influenced by the harmolodic music of Ornette Coleman, Shannon Jackson, James Blood Ulmer etc. We were playing tunes that were in tempo and time signatures, but he didn't really want anybody to be stating it. He used to say: "I can keep time, I don't need you to keep time for me! And I don't need the bass player to keep time, we can all keep time so let's just all play figures and ideas, the grid is in our heads, we don't need to state it." And that seems so obvious to me and I don't know why it seems in most music the drummer has to state the grid so explicitly. It's there and you can reference it, play against it or with it without someone having to outline it constantly for you.

If you have found an error or typo in the article, please let us know by e-mail info@insounder.org.