Milestones in Music History #42: Tōru Takemitsu, Achieving Beauty

The musical acumen expressed by the intuitions and innovations of Morton Subotnick, the talented musician we talked about in our last episode, opened new possibilities for experimentation, which in those years seemed to begin to take on a form of its own. Looking from the other side of the globe to the fascinating and mysterious land of the Rising Sun, experimentation and electronic music became a pure, delicate beauty. And this was possible only thanks to the prodigy Tōru Takemitsu.

The cosmos we live in is beautiful for its infinite facets. A melting pot of cultures, civilisations, traditions and languages. Although what is visible to our eyes is varied, there are universal concepts, such as peace, brotherhood, spirituality, love and beauty. These elements, common to all, are those that in some way enrich our life on this earth.

Among all those I have listed, beauty is perhaps the most ephemeral, as it transcends any dimension and has both subjective and objective value. And in my opinion, beauty finds a way to be most complete in music. Probably there doesn't exist such a thing as a perfect song, but there are melodies and compositions that we distinguish by a degree of pleasure, or rather, beauty.

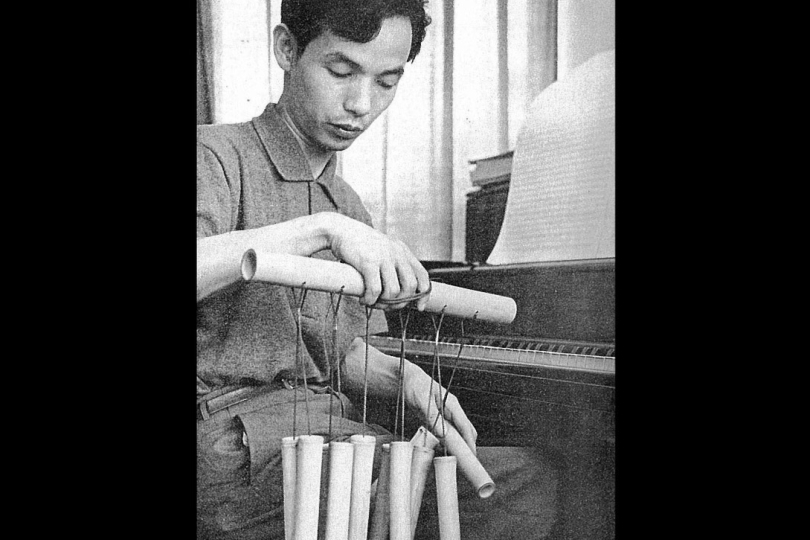

Sometimes, before the good, there is the bitter. And bitter was the experience – which he defined as such – of military service for Takemitsu, who was drafted at the tender age of 14. Probably a very traumatic experience, which at the same time had positive implications, since during the service he had the opportunity to learn about Western classical music, which he used to listen to in the form of a popular French song and with a handcrafted needle made from bamboo.

He was further introduced to Western music during the postwar American occupation of Japan, having taken a job with the US military. So, he tried to listen to foreign music as much as possible because Japanese music was too reminiscent of the bitterness of war. And so it was that he had the opportunity to get close to some of the great masters of classical music such as Arnold Schoenberg, Anton Webern and Edgard Varèse.

However, those who exerted the greatest influence on his early compositions were Olivier Messiaen and Claude Debussy, and at the age of 16, he knew his time had come. A perfectly conscious and deliberate choice, described by him as "my raison d'être as a man", and "the only thing" after the war. In the beginning of 1948, for a short time, he was educated in music by the composer Yasuji Kiyose, but almost immediately he left to dedicate himself to it as an autodidact.

Takemitsu began to delve into the discourse of technology in electronic music, focusing on the structure of sound and the way it is "deformed". He learned in those very years that in 1948 a certain Pierre Schaeffer had had the same intuition as him, with the development of musique concrète and he was thunderstruck. As we said before, common sentiments albeit from distant cultures.

To put his vision into practice in 1951, Tōru founded the Jikken Kōbō ("experimental workshop"), an artistic group that distanced itself from traditional Japanese music, but on the other hand imported music by contemporary Western composers, making it known in Japan. At the same time, Jikken Kōbō was an experimental forge, taking its cue from musique concrète and the music theory of Cage and his aleatoric music techniques.

It was during this period that they began using the tape-recording technique, which can be heard in compositions such as Vocalism A-I (1956) and Relief Statique (1955). But the work that made them famous overseas was his composition Requiem for string orchestra, which was heard by none other than Igor Stravinsky on his trip to Japan in 1958. Stravinsky admired the composition (to such an extent that he insisted on listening to the entire composition to the end) and praised Takemitsu's talents.

It was love at first sight, as they met immediately after the concert and Stravinsky invited Takemitsu to lunch (which Takemitsu himself called an "unforgettable" experience). It was probably also thanks to Stravinsky, with the help of Aaron Copland, that Takemitsu was commissioned a work by the Koussevitsky Foundation sometime later. To this end, he composed the beautiful Dorian Horizon in 1966.

As previously mentioned, Takemitsu initially rejected traditional Japanese music; however, starting from the early 60s, with the baggage of Western classical music he had listened to the years before, he began to approach his native culture, using traditional Japanese instruments, such as the biwa – a short-necked wooden lute that was traditionally used in storytelling – and becoming an appreciator of Japanese puppet theatre, the famous Bunraku.

But without forgetting the lesson of Schaeffer, Schoenberg and associates – and even of John Cage. Thus, one can find in his compositions some characteristics borrowed from the latter, such as the notion of emptiness and silence, and the emphasis on timbres conceived as individual sound events. In contrast, Cage took Zen from the East, which became an interest of his after he met with the Zen scholar Daisetsu Teitaro Suzuki.

A further musical experience that strongly conditioned Takemitsu was his participation in a gamelan show in Bali in 1972. There he understood how very different cultures have many common traits, and how gamelan scales and rhythms were not so dissimilar from traditional Japanese music, an integral part of Takemitsu's musical spirit.

So, in 1973 he wrote a piano solo for Roger Woodward entitled For Away, in which the structure of the notes that followed one another recalled the rhythms of metallophones, a typical gamelan instrument. And he felt at the same time a need to return to his roots, always composing in the same year one of his less-known works, Autumn, a piece for biwa, shakuhachi, and orchestra which resumed traditional motifs without forgetting the influence of Cage and musique concrète.

Takemitsu's musical works and his role as an avant-garde musician were already recognised in the early 1970s. The works of this decade revealed unprecedented experimentation and innovation. Starting with Voice (1971), for flute solo, and following with the dreamy compositions a few years later, Waves (1976) and Quatrain (1977).

But there was also a return to themes dear to the Japanese tradition, with a further interest in the garden, and all this produced two very intriguing compositions, Autumn Garden, for gagaku orchestra and A Flock Descends into the Pentagonal Garden. Listening to the compositions of this period, one gets the impression that different artists composed the musical pieces, of how varied themes, tones, timbres and motifs it is possible to find.

In the last phase of his production, starting from the 80s Takemitsu focused on the figure of the sea. More specifically, as he explained in a reading in 1984, he had managed to identify a common pattern in his compositions, which he defined as "total sea". An ascending succession of three notes which consisted of a half step and a perfect fourth, and in so doing created what he called the "sea of tonality".

But the connection to the sea, or to water in general, is also evident in the compositions of the period, Toward the Sea, Rain Tree, Rain Coming and I Hear the Water Dreaming. A very interesting work of his during these years was Dreamtime, an orchestral piece based on a trip he made to Groote Eylandt to visit a group of indigenous Australian singers, dancers and storytellers.

Takemitsu passed away before he could complete his last work, but his legacy is indescribable. He was a great innovator and important musician, who knew how to combine the cultures of the East and the West and then merge them into a beautiful sound embrace. He was able to make Japanese culture accessible to the contemporary and explain the reality of his time with ancient sounds and rhythms.

And finally, he was very versatile and had interests in many fields of art - and beyond. He composed music for over 100 films, a famous piece being the first battle scene of Kurosawa's masterpiece Ran. He dared like few others. But moving very far away, in the tanned West Coast of the 70s, we find some other shady figures who managed to turn the tide of music, ushering in surf punk. We will talk about Agent Orange, the protagonist of our next episode of Milestones.

How can you combine tradition and the future in the world of music today? What has changed in the way we enjoy music and art in general? Is it possible to innovate without denying one's roots? And what has been the contribution of Oriental music to the West?

Leave your opinion in the comments below!

If you have found an error or typo in the article, please let us know by e-mail info@insounder.org.